what can ara stakeholders do to ensure sustainability

Abstract

The highly globalized and competitive nature of the aircraft manufacture poses serious governance challenges. Recently, the utilize of voluntary measures, such as corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives, has been explored in terms of moving towards environmentally and socially responsible every bit well as safe shipping industry practices. Express attention has been paid on the role of stakeholders such every bit consumers, employees, NGOs, and academia in pressuring the shipping manufacture towards greater ecology and social responsibility. Here, by applying stakeholder theory and drawing on examples of already materialized stakeholder deportment and multi-stakeholder initiatives, we study the potential ways that stakeholders tin promote CSR in the shipping manufacture: we explore the resource dependencies between stakeholders, the stakeholder influence strategies, and the importance of multi-stakeholder pressure. We show that stakeholders tin proceeds more power by using indirect strategies such equally working via and/or in alliances with NGOs, trade unions, banks and financers, and/or different national or international regulatory bodies, every bit well as with the industry itself. Our results reveal the potential of multi-stakeholder pressure and activeness to promote the adoption of CSR activities, support the transparency, legitimacy, and enforcement of the practices, likewise equally widen the scope and focus of CSR initiatives and practices by focusing on a wide range of social and environmental issues. Finally, stakeholder pressure can push towards improved regulations. The study suggests that increased attention needs to be paid on the multi-stakeholder demands, especially because the accentuated importance of constructive maritime governance in the futurity.

Introduction

The shipping industry is a highly globalized, competitive, and dynamic manufacture: global shipping transports effectually 90% of world merchandise (ICS 2014). All the same, the various environmental impacts of the aircraft industry are severe, including air pollutant emissions (such as sulfur and nitrogen oxides and carbon dioxide), oil and chemic cargo discharges, and litter, sewage, and invasive species in ballast water (Andersson et al. 2016). Furthermore, the industry is characterized by the wide abuse of maritime policies with the use of flags of convenience to avoid national or regional regulation such equally Flag State Control measures, taxation evasion and the utilise of revenue enhancement havens, and the inadequacies and abuse of Port State Control measures. All of these have further contributed to reduced safety levels of shipping activities, social problems such as poor working conditions, and loftier environmental impacts and risks (Kuronen and Tapaninen 2009; Roe 2008; Sampson and Bloor 2012).

International maritime policies and regulations are mainly set past the Un' International Maritime Organization (IMO) and entered into forcefulness by nation states. The principle IMO conventions in terms of safety and the environment include the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL), the Convention for Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS), and the International Convention on Standards of Grooming, Certification and Watch keeping for Seafarers (STCW). Still, the IMO regulatory framework has been increasingly criticized for its ineffectiveness in addressing the ecology impacts or the social bug of aircraft, such as labor rights problems, as well as ensuring condom at ocean: these accept remained every bit static, height-downwards policies, and too slow to react to changes in the industry (Roe 2013; Kuronen and Tapaninen 2009). For instance, the ratification processes of IMO conventions are slow or the conventions are not entered into forcefulness due to insufficient ratification among the member nations (Lister et al. 2015). In add-on, at that place is a lack of clear enforcement of the adopted regulations (Det Norske Veritas 2014).

As a response to the failure of IMO regulation, various means to improve safety and to reduce the ecology bear upon of aircraft have been proposed. Kuronen and Tapaninen (2009) projected a need to change the whole safety authorities. Roe (2008, 2013) proposed developing a maritime governance organisation towards multi-level or polycentric governance, and Haapasaari et al. (2015) discussed the potential of a regional risk governance framework in enhancing safety.

Several authors have discussed the part of cocky-regulation and voluntary actions, such as corporate social responsibility (CSR) practices, in the shipping industry (Fafaliou et al. 2006; Wuisan et al. 2012; Yliskylä-Peuralahti et al. 2015). CSR activities are voluntary initiatives that provide industries and companies with one way to account for environmental and social issues in their economic activities (Aguilera et al. 2007; Aguinis and Glavas 2012; Dahlsrud 2008; McWilliams et al. 2006). Compared to land-based industries, the office of CSR practices has remained limited in the shipping industry (Det Norske Veritas 2014; Lister et al. 2015; Yliskylä-Peuralahti and Gritsenko 2014).

In that location is a lack of comprehensive analyses in the literature on the potential ways to initiate the use and adoption of CSR practices in the aircraft industry. While some studies have examined the office of industry alliances (Lai et al. 2011; Poulsen et al. 2016), the role of stakeholders from exterior the industry, including, NGOs, media, consumers, and local communities in pressuring the shipping industry, has largely been neglected. At the same fourth dimension, tighter co-operation between the different stakeholders in the aircraft industry besides as extending and deepening stakeholder interest in maritime governance is considered necessary (Roe 2013; UNCTAD 2015; Yliskylä-Peuralahti and Gritsenko 2014). The aim of this paper is to examineand discuss the potential of multi-stakeholder alliances betwixt both the primary stakeholders (often financial such every bit shareholders, employees, or customers) and secondary stakeholders (often non-financial such as NGOs, media, and consumers) to promote CSR in the shipping sector. Here, nosotros identify particular accent on the resource dependencies between stakeholders, stakeholder influence strategies, and the importance of multi-stakeholder pressure and co-operation. The potential role of the scientific community in the process is discussed.

The paper is based on an extensive literature review. To examine the potential ways in which stakeholders tin can promote CSR in the aircraft manufacture, nosotros apply stakeholder theory as an analytic tool. Originated past Freeman (1984), the theory provides a framework for exploring how stakeholders influence firms. Stakeholder theory allows for a new and original way of approaching the question of how stakeholders can proceeds influence over the shipping industry: nosotros consider the office and influence of stakeholders in the shipping sector in terms of resource dependence (Frooman 1999), search for the central dependencies and advice paths among them, and examine the role of both primary/financial and secondary/non-financial stakeholders. Based on the results, we advise novel steps for promoting CSR in the shipping sector.

In Sect. 2, we introduce the concept of corporate social responsibility, which has only recently gained some ground in the shipping industry. In Sect. 3, stakeholder theory is practical to identify the potential direct and indirect strategies for stakeholders to pressure industries and corporations into adopting environmentally and socially responsible practices. In Sect. 4, by applying stakeholder theory to the shipping industry, we synthesize and analyze a range of already materialized voluntary stakeholder-driven measures and multi-stakeholder initiatives in the industry. In Sect. v, nosotros summarize the roles of different stakeholders and bring forward the potential significance of multi-stakeholder pressure. Finally, in Sect. half dozen, we provide a road map for further actions and discuss the benefits and limitations of stakeholder participation in developing CSR initiatives in the shipping industry. Section vii identifies the future inquiry needs and the growing importance of voluntary stakeholder-driven measures in promoting environmental and social responsibility in the shipping industry.

Corporate social responsibleness and the shipping manufacture

Corporate social responsibleness

The use and implementation of CSR practices in unlike industries has been widely studied (Aguilera et al. 2007; Aguinis and Glavas 2012; Dahlsrud 2008; McWilliams et al. 2006). The theoretical perspectives on the apply of CSR are varied and have changed through time and space (McWilliams et al. 2006), and no clear-cut definitions exist for CSR. Most normally, however, CSR is defined as situations where corporations appoint in voluntary actions going "across compliance" or regulations by actively incorporating social and environmental concerns in their business operations (McWilliams et al. 2006).

In addition to various international, national, or industry-specific guidelines, such equally the United Nation'south (Un) Global Compact or the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises, CSR methods and initiatives ofttimes include fiscal drivers, environmental and social standards/certifications, and the forming of business organization associations (Ranängen and Zobel 2014).

Land-based industries with extensive environmental and social impacts, such as the extractive industries, habiliment and retail industries, or chemical product, have been at the forefront in developing CSR practices. Land-based industries accept often adopted formal written codes of environmental and social responsibility. Some of the about comprehensive CSR practices can exist found in the oil and gas industry, but the forest industry is also guided by diverse initiatives such every bit woods certifications and eco-labeling (Ranängen and Zobel 2014; Sharma and Henriques 2005). Brand retailers such as Walmart and Unilever accept recently emerged equally CSR leaders (Dauvergne and Lister 2013).

CSR in the shipping industry

The part of self-regulation and the adoption and implementation of CSR activities in improving condom and reducing the environmental impact of aircraft has gained increasing interest among the different actors in the shipping manufacture, equally well as in academia (Acciaro 2012; Kunnaala et al. 2013; Poulsen et al. 2016; Yliskylä-Peuralahti et al. 2015).

In full general, environmental and social responsibleness in the shipping industry has been found to be motivated by the need to comply with existing and possible future regulations, but likewise the desire to identify efficiency gains with the use of environmental strategies likewise equally the goal to proceeds competitive advantage by establishing a green image (Acciaro 2012). A socially responsible aircraft company hither refers to a company that actively incorporates social and environmental concerns in its business operations and that, in add-on to the fiscal stakeholders, such every bit transport owners, shareholders, ports, customers, financers, insurers, and classification societies, besides pays attending to the interests of the not-financial stakeholders, such as different environmental and societal stakeholder demands.

Still, there are several limitations to the utilise and effectiveness of CSR practices. Some CSR activities have been considered merely as forms of greenish-washing, i.east. the gap between physical deportment and symbolic "green" talk (Lyon and Montgomery 2015), besides as the extent to which CSR practices have been effective in changing industry practices, has remained unclear and is continuously debated (Aguilera et al. 2007; McWilliams et al. 2006; Ranängen and Zobel 2014). Similarly, in the shipping industry, the extent to which companies take understood the benefits of CSR practices, as well as the extent to which these can exist beneficial, for case, in increasing safety or protecting the environment, is non always clear and there is limited empirical information on the benefits of CSR for shipping businesses (Fafaliou et al. 2006).

The highly globalized, dynamic, and competitive nature of the aircraft industry poses meaning challenges to the adoption and implementation of the CSR- framework: due to the highly competitive environment, shipping companies tend to seek brusk-term profit, whereas engaging in CSR activities generally produces economic, social, and environmental value in the long term (Kunnaala et al. 2013). Furthermore, both the geographical and regulatory context makes CSR implementation circuitous. In general, CSR practices in aircraft have been found easier to implement in countries and regions where strict regulations and high environmental standards already exist (Yliskylä-Peuralahti et al. 2015).

In that location are besides differences betwixt shipping and operation types. For example, quality standards for oil and chemical tankers are more stringent than those for container or dry bulk ships, and they undergo a number of quality inspections such equally classification, port inspection, and vetting practices, where the higher tanker safety standards have led to meaning reductions in oil spills (Poulsen et al. 2016). Oil spills are immediately visible to the public, and these improvements are generally considered every bit the results of joint activity between the public, policymakers, and cargo-owners driven by high media visibility (Poulsen et al. 2016).

While oil spill prevention has largely remained the only business organisation in terms of tanker shipping, the container sector has focused on a wider variety of environmental bug (Poulsen et al. 2016). However, the environmental impacts of dry majority aircraft, including COtwo emissions, invasive species, or the scrapping of vessels, have remained less visible and accept been considered largely neglected by the industry, regulators, and public attention (Poulsen et al. 2016).

In improver, even though CSR practices have largely been motivated by the possibility to proceeds competitive advantage by paying attending to the ecology impacts of the industry, limited attention has focused on the different social issues, including safe at work, labor rights bug, client relations, the affect of aircraft on coastal communities, and the increased transparency of operations (Acciaro 2012; Det Norske Veritas 2014; Roe 2013; Yliskylä-Peuralahti et al. 2015). Fifty-fifty though different forms of international legislation already be in terms of, for case, increasing the safety of shipping crew, such equally the IMO SOLAS (International Convention for the Safety of Life at Ocean) Convention, there is a lack of clear enforcement of these practices (Det Norske Veritas 2014).

Stakeholder participation has been emphasized in the various definitions of CSR (Dahlsrud 2008), and it is argued that in order to understand the full societal benefits and implications of the use of CSR, more attention needs to exist paid to the function of unlike stakeholders (McWilliams et al. 2006). Shipping has generally been considered equally a business concern-to-business industry, where non-fiscal stakeholders have limited influence on industry practices (Acciaro 2012; Poulsen et al. 2016). However, the role of both industry stakeholders and the different secondary/non-financial stakeholders in demanding safety and sustainable shipping practices is increasingly emphasized, for instance by calling for a multi-stakeholder arroyo and effective data collection, sharing, and broadcasting in the shipping industry in social club to heighten sustainable maritime transport (UNCTAD 2015).

Roe (2013) argues that the range of stakeholders needs to be extended in improving shipping governance, including the media, politicians, and various interest groups. Similarly, Haapasaari et al. (2015) have argued for regionally constructive proactive maritime rubber governance based on wide-ranging stakeholder participation, and according to Yliskylä-Peuralahti and Gritsenko (2014), there is a need to broaden the telescopic of governing actors and governing instruments, and for closer cooperation and delivery of different stakeholders in governing the shipping industry. By analyzing the different influence strategies and relationships of resources dependence between stakeholders, this written report explores the potential of stakeholder alliances to proceeds influence over industry practices and highlights the opportunity of multi-stakeholder pressure to improve and pressure level the aircraft manufacture into incorporating greater social and environmental responsibility in its actions.

Stakeholder direction theory

Stakeholder theory can be used to identify unlike stakeholders inside and outside a firm that influence the firm and to explain the types of influence that the different stakeholders exercise over the firm's sustainability practices (Freeman 1984; Frooman 1999; Phillips et al. 2003). Stakeholders are generally classified either equally chief stakeholders, who are engaged in a formal relationship with the firm (due east.thou., shareholders, employees, suppliers, customers, and government bodies) or secondary stakeholders, who have no formal relationship with the firm (e.k., media, NGOs, citizens, and the local community) (Clarkson 1995). Fifty-fifty though the latter (often non-financial stakeholders) have largely been considered as secondary by managers in the past, these groups are now becoming more salient in terms of assessing the social and ecological impacts of concern (Sharma and Henriques 2005). The theory focuses on balancing stakeholder interests given the extent of the impact on stakeholders and their influence, i.e., based on criteria rather than seeking residuum in a strict sense. Incorporating the broad range of stakeholders demands is considered essential in improving industry practices and supporting the legal and moral interests of stakeholders (Phillips et al. 2003).

The influence strategies that stakeholders use depend on the resources relationship they have with a business firm and can therefore either be straight or indirect (Frooman 1999). Stakeholders can exist either dependent on or contained of the firm, similarly, a firm tin be dependent on or independent of the stakeholders. Therefore, iv scenarios of resource interdependence exist between firms and stakeholders: high resource interdependence, low resource interdependence, business firm power, and stakeholder ability (Frooman 1999) (Table one).

Loftier interdependence

When in that location is high interdependence between the focal business firm and its stakeholders, the near likely strategy for the stakeholders is to straight influence the firm's employ of resource and to redefine the common goals. Direct strategies refer to stakeholders themselves manipulating the flow of resources to the house. Usage strategies refer to strategies where stakeholders continue to supply a resource, just with strings attached, for case, demanding a change in industry practices (Frooman 1999). Every bit both the stakeholders and the firm are dependent on each other, the stakeholders are not able to shut off the flow of resources to the firm. In addition, the cost of changing industry practices tends to be shared between the stakeholders and the firm.

1 example of high interdependence is the formation of strategic alliances and international networks between the industry players themselves, or competitors in order to address environmental problems (Buysse and Verbeke 2003). In fact, there is a tendency for individual managers and firms not to ameliorate their practices earlier their industry acts collectively (Aguilera et al. 2007). The dominant primal players forming alliances too have an of import role in disseminating and diffusing CSR practices within industries (Delmas and Toffel 2004), whereas companies resisting the adoption of sustainability practices are in danger of negative corporate reputation which has an touch on firm survival and profitability (Sharma and Henriques 2005; Clarkson 1995).

Stakeholder power

If stakeholders command disquisitional resources, merely are not dependent on the firm, they tin can withhold the resources from a focal firm unless it follows certain rules. Withholding strategies are defined as those where stakeholders discontinue or threaten to discontinue providing a resources to a house if the house is non willing to change its beliefs. With withholding strategies, the firm would be expected to pay the costs of new practices. Withholding strategies include consumer pressure, where consumers exert negative pressure and boycott companies with poor ecology records (Aguilera et al. 2007; Buysse and Verbeke 2003; Sharma and Henriques 2005). For instance, Greenpeace led a boycott campaign confronting Nestlé, as the visitor used unsustainable palm oil sourced from Indonesia—the campaign resulted in Nestlé adopting new sustainability practices and working towards ending the employ of unsustainable palm oil (Greenpeace 2010; Ionescu-Somers and Enders 2012).

Firm power

Under the tertiary scenario, the firm and its stakeholders are considered to accept no interdependence. Examples include firms or companies operating in a highly competitive environs with lax regulations. Here, indirect and usage strategies are likely to be used by stakeholders, such as hands replaceable employees (versus managers) or minor suppliers. Since the business firm has no resource dependence on the stakeholder groups, the firm'south sustainability practices are unlikely to exist influenced by stakeholder force per unit area (Frooman 1999). However, declining to support stakeholder participation and direction strategies can erode relationships or amerce stakeholders altogether (Hosmer and Kiewitz 2005), or atomic number 82 to the increased use of confrontational strategies by stakeholders such equally strikes (Mitchell et al. 1997; Sharma and Henriques 2005).

Low interdependence

When focal firms and stakeholders take no interdependence, indirect strategies via other stakeholders are likely. Indirect strategies refer to stakeholders working in alliances or via other stakeholders to influence industry practices. Environmental groups tin can force per unit area governmental agencies or large buyers/customers to only operate with companies that adopt sustainable practices. For example, ecology groups targeted large buyers such as Domicile Depot and Lowe'south in the United states so that they would only purchase forest products from Canadian companies that had adopted sustainable practices (Sharma and Henriques 2005). Similarly, stakeholder alliances can pressure banks and financers to divest from companies or projects that are not considered responsible.

Stakeholder groups are not static: fifty-fifty if stakeholders, such every bit easily replaceable employees, initially have little ability, they tin can acquire more past working in alliances or influence industry via other stakeholders (Frooman 1999; Mitchell et al. 1997). In fact, multi-stakeholder dialogue and action accept been found effective in pressuring corporations to move towards incorporating greater social and ecology responsibility in their actions (Byster and Smith 2006; Connor 2004; Kong et al. 2002; Raphael and Smith 2006). This is illustrated, for case, the Silicon Valley Toxic Coalition (SVTC) created in response to the use of hazardous chemicals by the electronics industry in the Silicon Valley: the combined pressure level of the industry worker's rubber advocates, local community activists, community residents, high-tech workers, union members, fire fighters, policymakers, and later on primary stakeholders such equally unlike engineering companies, resulted in a change in practices in the electronics industry. Finally, the pressure led to the adoption of new legislation, such equally Extended Producer Responsibleness (EPR) requiring the recycling of electronic waste (Raphael and Smith 2006; Byster and Smith 2006).

Similarly, Sharma and Henriques (2005) found that in the woods industry, the more avant-garde sustainability practices,such as eco-pattern or ecosystem stewardship, were based on pressures from both withholding influence strategies from secondary, not-financial, stakeholders (such as consumers, media, local communities, activist shareholders, ecology and social NGOs, special interest groups, and indigenous people), and usage influence strategies applied by primary financial stakeholders, such as customers.

Stakeholder influence in the shipping industry

4.1. High interdependence

Industry alliances

The central aircraft companies working in alliances have an important role in disseminating and diffusing CSR practices within the aircraft industry (Table 2). Recently, the International Chamber of Shipping (ICS), the principle international trade association for the shipping industry, committed to reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from the international shipping sector (IMO 2016). This commitment, even though a separate initiative, is consistent with the goals of the UFCCC Paris Understanding (COP 21). Similarly, the Norwegian Shipowners' Clan (NSA) has been proactively involved in calling for international regulation on issues such every bit the scrapping of ships and handling of ship anchor h2o (Norwegian Shipowners' Association 2016), and the association was one of the driving forces behind the IMO Hong Kong International Convention for the Prophylactic and Environmentally Sound Recycling of Ships (HKC), which was adopted in May, 2009.

Another instance of an industry brotherhood is the Make clean Shipping Projection (CSP) (Table 2). The CSP is a business organization-to-concern initiative established in Sweden in 2007 that aims to increase focus on the environmental issues associated with shipping and to improve the ecology functioning of marine container transport.

Even so, initiatives often suffer from a lack of enforcement mechanisms (Lister et al. 2015). Interestingly, there is an example of an industry brotherhood that especially focuses on the enforcement of regulations: the Trident Alliance is a coalition of mainly Scandinavian shipping owners and operators, and information technology is committed to the transparent enforcement of maritime sulfur regulations, such every bit the IMO's SECA (Sulphur Emission Control Area) regulations (Trident Alliance 2016).

Customers

Some shipping firms are also starting time to prefer dark-green practices in the face of increasing environmental requests from customers, such equally cargo-owners and business concern partners who have a vested interest in their ecology and productivity performance (Lai et al. 2011; Poulsen et al. 2016). Hither, cargo-owners generally apply straight usage strategies: the customers demand a modify in practices, just due to the resource dependence, they are not able to withhold the supply of resources.

The demands from cargo-owners accept resulted in several shipping rating schemes (see Table 3). As a function of the Make clean Shipping Project, the Clean Shipping Alphabetize (CSI) has been developed, where cargo-owners can select high-ranking shipping companies based on the index: the shipping companies can gain competitive advantage by adopting techniques and practices to reduce the environmental bear on of aircraft (see Table 3). The CSI therefore creates incentives for other shipping companies to improve their ranking by investing in pollution control measures (Wuisan et al. 2012). Similarly, for instance, Walmart, the earth's largest retailer, requires shipping companies to be registered under the Make clean Cargo Working Grouping (CCWG) (encounter Table 3): the CCWG is a business concern-to-business initiative defended to improving the environmental functioning of ships and uses a rating scheme to benchmark shipping companies confronting industry standards. The CCWG represents fourscore% of sea container cargo carriers including 20 of the world'south largest container shipping lines (Make clean Cargo Working Group 2016).

Apart from the CCWG and ShippingEfficiency.com initiative (providing GHG emission information and ratings for more than 60,000 vessels), the schemes have only started to influence environmental protection in shipping: they cover but a small share of the world fleet, which in full comprises more than 47,000 commercial vessels (of 1000 GT and above) (Poulsen et al. 2016).

Ports can act as leaders in sustainable practices, and the role of ports in sustainable supply chain direction has increasingly been explored (Denktas-Sakar and Karatas-Cetin 2012). For instance, the Green Award promotes the highest standards in ecology performance and safety in shipping by rewarding operators who have received the Green Award certification with different discounts and incentives (Green Laurels 2009) (see Tabular array iii). Ports and other industry actors can provide incentives for vessels that have been awarded with Green Award, such equally discounts in harbor dues, lower insurance premiums, or a reduction in the send's tonnage fee. Similarly, the Ecology Ship Index, which is a benchmarking tool launched by the World Ports Climate Initiative (WPCI), offers vessels with the low emission levels a reduction in port fees. Despite these initiatives, ports have been considered to have a limited influence and to play but a minor office in promoting green practices (Poulsen et al. 2016).

Banks, financers, and classification societies

Send owners and operators largely rely on the banking sector to invest in environmentally friendly technology helping the ships to relieve on fuel use and reduce air emissions. Fiscal institutions generally perceive companies with a poor environmental record equally riskier to invest in and may therefore need a college-risk premium, not invest, or refuse to extend new loans (Buysse and Verbeke 2003). Consequently, commercial banks could play a key office in financing energy-efficient maritime transport systems (UNCTAD 2015). Every bit important sources of funding, individual funds and commercial banks could too ready higher standards of condom functioning every bit part of the conditions for loans to aircraft companies. Classification societies, such as Lloyd's Register, provide assessments and certifications of different international safety and environmental standards for the pattern, structure, and operation of ships, e.thousand., different ISO standards (Lloyd's Annals Marine 2016). In addition, Lloyd'southward register has adult its own safe standards. The classification societies could play an important function in improving standards, schemes, and directives in the shipping manufacture.

Stakeholder power

Consumers are increasingly conscious of the ethical and environmental impacts of products and services, and consumer power can take a profound influence on visitor practices. Consumer pressure in the shipping industry has been considered low due to the business-to-concern nature of the industry, every bit well as the low media visibility of the environmental impacts of aircraft (Yliskylä-Peuralahti and Gritsenko 2014; Poulsen et al. 2016). Compared to other shipping industry sectors, the cruising industry sector provides an interesting case in terms of consumer pressure level: in that location is a tighter link between the industry and the consumers and, for instance, straight withholding influence strategies such as consumer boycotts could effectively pressure cruise ships into adopting CSR initiatives. Serious attention has been paid on marine condom on prowl ships and cruising is considered a very safe method of traveling (Cartwright and Baird 1999; Lois et al. 2004). Every bit will be illustrated afterwards, consumers can besides apply indirect strategies and work in closer co-operation with other stakeholders such as customers, NGOs, media, and regulators and/or influence the shipping industry via these more powerful stakeholders.

House power

Nether the 3rd scenario, where a firm has no resource dependence on the stakeholder group, the house's sustainability practices are unlikely to be influenced by stakeholder pressure (Frooman 1999). Ship-owners/shipping companies are in a very powerful position in the shipping industry: globalization has enabled ship-owners to take advantage of the regulatory framework and the competitive nature of the manufacture, i.east., the national flag registers enable the ship-owners to select between countries when registering their fleet (Roe 2013). Consequently, at that place are two types of companies competing with each other in the shipping market: those companies that are responsible and focus on high-quality shipping and those that focus on providing low-cost services at the expense of safety and the environment (Yliskylä-Peuralahti et al. 2015). The latter are unlikely to be influenced by stakeholder demands.

Furthermore, employee demands are unlikely to influence the companies: under globalization and the relaxed regulatory requirements, seafarers are being sourced from new labor supply nations such as Philippines with comparatively lower salaries (Progoulaki and Theotokas 2010). In improver, the size of the shipboard coiffure has been dramatically reduced and the profession tends to be characterized by relatively inferior working conditions and high insecurity due to short-term contracts and a high crew turnover (Bhattacharya 2011; Progoulaki and Theotokas 2010). Even though the companies are unlikely to solely be influenced by employee demands, employees can gain power by using indirect strategies: as will be shown afterwards, employees need to piece of work in alliances and be supported past NGOs, trade unions, and/or unlike national or international regulatory bodies.

Low interdependence

In the shipping industry, various examples of successful NGO campaigns and alliances exist where NGOs have used indirect withholding strategies and worked in alliances or via other stakeholders to influence industry practices. NGOs take raised awareness of a broad agenda of environmental and social bug in shipping and have gained power and legitimacy by allying with other NGOs, the public, and/or with transnational regulatory bodies, such as the IMO or the European Commission.

The Make clean Ship Coalition (CSC) is a global coalition of several NGOs focusing on a variety of environmental and social bug in shipping, including the protection of marine and atmospheric environments, the safety of shipping operations, sustainable development, and social and economic justice, every bit well as human health. The CSC was granted IMO observer status in 2010. In addition, the Seas at Risk, a European association of non-governmental environmental organizations, works on multiple maritime bug and launched the "Clean Ship" concept in 2002 focused on ship waste dumping: as a result of agile lobbying, the concept was included in the European Commission'due south Communication on an integrated maritime policy for the EU (Seas at Risk 2015). Similarly, the World Broad Fund for Nature (WWF) has globally campaigned for improvements in the shipping industry in terms of calling for sustainable shipping, amend practices, and putting an end to flags of non-compliance (WWF 2015). WWF also works together with the IMO and was active, for example, in pushing for the Convention on the Control of Harmful Anti-fouling Systems on Ships, which entered in force globally in 2008 (WWF 2015). In addition, WWF is working with the Sustainable Shipping Initiative, as will exist illustrated later.

In terms of the cruise manufacture, in 2004, the international ocean conservation group, Oceana, successfully persuaded Miami-based Royal Caribbean area, the world's second largest prowl ship company, to install wastewater handling technology in its fleets, and later on that year, the state of California passed legislation to stop sewage dumping by cruise ships (Oceana 2004). In the Baltic Sea, following a long HELCOM (the Baltic Marine Environs Protection Commission) process aiming to limit sewage discharges in the Baltic, also equally NGO campaigns (e.1000., WWF campaigns) and media attending, all sewage discharges from passanger ships will be banned, as the Baltic Sea special area for sewage discharges from passenger ships under the MARPOL Convention volition come into force by 2021 at the latest (HELCOM 2016). Currently, just 30% of international cruise ships in the Baltic Sea have been reported to use the port reception facilities (HELCOM 2016), while the residuum empty sewage directly into the sea.

NGOs and syndicate organizations have too focused on improving social problems and labor rights in the shipping industry. The NGO Shipbreaking Platform is a coalition of nineteen environmental, human rights, and labor rights organizations that aim to stop the dangerous pollution and unsafe working atmospheric condition in shipbreaking. The NGO monitors ship-owners and shipping companies and has launched the OFF THE Beach website, which is targeted at cargo-owners and the public, and provides information on ship-owners (NGO Shipbreaking Platform 2016a). The NGO has also backed a new European Commission Report recommendation for the use of a ship recycling license to promote sustainable shipping recycling: the aim is for all the EU ports to require the license, regardless of the flag of the send. The current 2013 Eu Transport Recycling Regulation requires all vessels sailing under an Eu flag to employ an approved ship recycling facility, all the same, the regulation tin can but be circumvented past flagging out and using flags of convenience. Therefore, the ship recycling license could provide an effective way of enforcing the polluter pays principle (NGO Shipbreaking Platform 2016b).

Also, the human being element and seafarer'south rights are now recognized equally existence closely linked with safety (Sampson and Bloor 2012; Hetherington et al. 2006), and organizations such equally the European Transport Worker'due south Federation (ETF) are working on improving European union labor rights and legislation to as well include maritime transport workers. The ETF has pressed for the adoption of a wider regulatory framework in which the competitiveness of the shipping manufacture would be based on the highest possible standards of prophylactic in both environmental and social terms (European Ship Workers' Federation 2015).

Multi-stakeholder co-performance, including both industry and not-financial stakeholders, and the combination of pressure have the potential to alter shipping industry practices. The Sustainable Shipping Initiative (SSI), initiated by a non-profit system, Forum for the Futurity, is an example of multi-stakeholder co-operation representing a cross-industry group of transport owners, charterers, transport builders, engineers, banking, insurance, and classification societies, besides as the World Broad Fund for Nature(WWF) (Forum for the Futurity 2017). Major industry representatives such equally Maersk Line, Cargill, Lloyd'southward Annals, Wärtsilä, and Namura Shipbuilding are part of the plan. The initiative addresses the economical, social, and environmental challenges facing the industry, and is working towards a sustainable shipping industry past 2040 and contributes to the Un Sustainable Development Goals (Forum for the Future 2017).

Finally, the World Sea Quango (WOC) aims at establishing collaboration to address different marine environmental challenges. The WOC is an international business alliance that brings together leadership companies from beyond the diverse ocean business concern community to develop industry collaboration in body of water sustainability, science and stewardship. It is a private sector initiative, but the members include commercial, academic, and institutional organizations (World Bounding main Council 2017).

Post-obit the 1989 Exxon Valdez incident in Prince William Sound, Alaska, where an estimated 42 million liters (11 million gallons) of crude oil was spilled in the sea, the local residents gained an marry in the government: the stakeholders became influential by receiving support from more powerful stakeholder groups such every bit the Alaska Land government and the court system (Mitchell et al. 1997). An of import outcome was the Oil Pollution Deed of 1990 (OPA), which provided the federal authorities more legislative power over maritime oil transportation. Furthermore, a stakeholder Steering Committee was formed involving a broad range of stakeholders, including shipping companies, government, the oil industry, local industries, local citizens, representatives of environmental conservation, and the declension baby-sit (Merrick et al. 2001; Merrick et al. 2002). The project was based on cooperative risk management, and the involvement of all stakeholders was constitute to accept resulted in the acceptance of high levels of investment to reduce the hazard of farther oil spills.

The importance of stakeholder influence

Globalization, the highly competitive environment, and the weak regulatory framework have contributed to a situation where responsible shipping companies and companies focusing on curt-term gains compete in the field of maritime transport. Ship-owners can past themselves or past co-operating with each other in alliances disseminate and diffuse CSR practices within the industry. However, the industry initiatives tend to be limited by the relatively low number of companies participating in them, the lack of enforcement mechanisms, as well every bit the reluctance of low-toll companies to invest in improving their practices. The testify from this report suggests that multi-stakeholder force per unit area tin can promote the adoption, implementation, and enforcement of CSR practices in the shipping industry.

This study indicates that customers, such as cargo-owners and business organisation partners, can be highly influential if they require responsible practices from the shipping companies they bargain with. For case, dry out bulk shipping has been mentioned every bit a sector that is lagging behind in terms of developing sustainability practices (Poulsen et al. 2016), and customer pressure could therefore enhance CSR compliance to get a status of entry in market place partnerships. In addition, the role of ports in sustainable supply chain management can exist pregnant as they can provide incentives for vessels that are committed to sustainable practices. The banking sector has a central office in focusing its financing on free energy-efficient and ecologically friendly maritime transportation that also accost the well-being of crews. Nomenclature societies accept the power to set strict safety and ecology standards for the design, construction, and functioning of ships.

Consumers, on the contrary, have more often than not had a limited role in pressuring the shipping industry, although raising consumer awareness of sustainable consumption can to some extent promote the adoption of environmentally and socially responsible practices, particularly in the cruising sector. In the current situation where seafarers are oft sourced from low-salary countries, the employees have also had very little influence overthe manufacture practices.

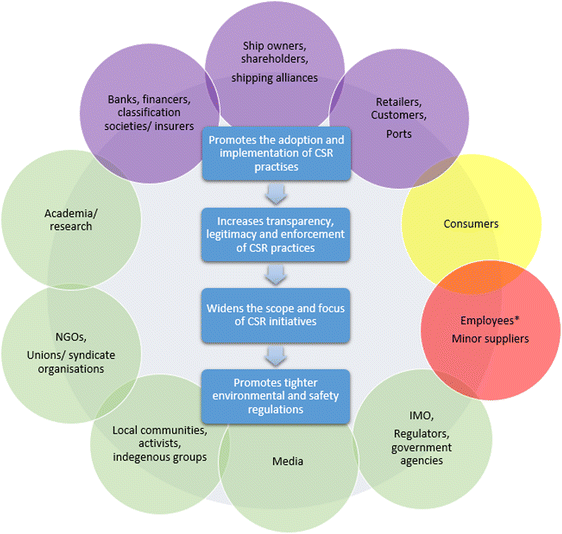

This written report has demonstrated how consumers and employees tin gain more ability by using indirect strategies such as working in alliances with NGOs, trade unions, banks and financers, and/or unlike national or international regulatory bodies, as well as with the industry itself. The analysis indicates that multi-stakeholder dialog and activeness (including both financial and non-fiscal stakeholders) and the combination of pressure can exist an influential manner to force per unit area the industry into incorporating greater social and ecology responsibleness in its actions (Fig. 1). Alliances betwixt the industry, consumers, local communities, NGOs, merchandise unions, banks and financers, and policymakers can support the adoption and implementation of CSR practices, increment the transparency, legitimacy, and enforcement of the practices, and contribute to wider discourse on sustainability by focusing on a broad range of social and environmental issues.

Multi-stakeholder pressure. Loftier interdependency (purple), stakeholder ability (yellow), firm power (cerise), and low interdependency (greenish). *Employees here refer to easily replaceable employees (vs. managers)

Finally, multi-stakeholder pressure, based on both primary/financial and secondary/non-financial efforts, can lead to advanced sustainability practices and improved regulations: CSR practices help the adoption of new technological improvements, e.g. eco-ships or the use of culling fuels, simply more importantly, CSR practices based on stakeholder force per unit area, including co-operation with regulators, can be considered equally important stepping stones towards tighter social and environmental regulation.

Towards multi-stakeholder pressure

Our analysis has revealed the potential for multi-stakeholder co-operation and pressure to promote environmental and social responsibility in the shipping industry. The shipping industry has generally been considered equally a business-to-business organisation industry, where non-financial stakeholders accept had limited influence over industry practices, and pressure from outside the visitor has seldom been considered to motivate companies to engage in CSR activities (Poulsen et al. 2016; Kunnaala et al. 2013). For instance, even though improvements in terms of oil and chemical tanker safe have been viewed equally the results of the joint activeness between the public, policymakers, and cargo-owners, this has been considered every bit a special instance. In comparing to other environmental impacts, oil spills frequently accept high public visibility as they attract wide media attention (Poulsen et al. 2016).

Yet, nosotros take shown that stakeholders, i.e., consumers or employees with limited initial power, can piece of work in alliances with other stakeholders and/or potentially effectively pressure the manufacture via other, more powerful, stakeholders. The shipping industry may non be straight faced by secondary/non-financial stakeholder demands, merely the customers are, and the manufacture therefore also remains to exist afflicted by other than chief/fiscal stakeholder demands. Furthermore, while stakeholder pressure might non have been considered relevant before, the pressure from both industry stakeholders and non-financial stakeholders has increased in recent years (Kunnaala et al. 2013). Manufacture initiatives are also increasingly co-operating with non-financial organizations. For example, even though the World Sea Council (WOC) was developed by the private sector, the WOC network now includes over 35,000 ocean industry stakeholders globally, including intergovernmental bodies, governments, and NGOs (WOC 2017). Therefore, we consider that attending to the different stakeholder demands will exist increasingly important for companies that wish to adopt and implement CSR practices and gain strategic benefits past doing so.

Nosotros have demonstrated different types of stakeholder dependencies and stakeholder influence strategies in the aircraft sector. Nevertheless, the resource dependency system is complex and the dependencies are not static: resource relationships are constantly changing and dynamic in exercise. For example, if access to oil reserves is limited due to, due east.g., political instability, the relationships are probable to move towards firm power. On the other manus, every bit new technology is developed or consumer behavior changes due to, due east.grand., NGO and media campaigns, the demand for oil decreases and we motility towards stakeholder power. Due to this complexity, describing and analyzing the organization, remains a challenge.

In contrast to well-nigh land-based industries that accept all-encompassing CSR frameworks, the use of responsibleness practices has only recently gained some ground in the shipping manufacture. Bear witness of the touch on of CSR practices on the efficiency and functioning of companies remains scarce. Scientific research is needed to shed light on the short- and long-term impacts of CSR practices and reduce the uncertainty faced past shipping companies related to investments in responsible practices.

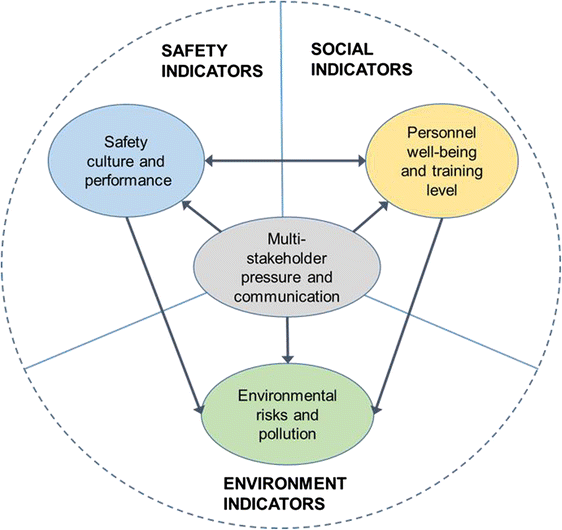

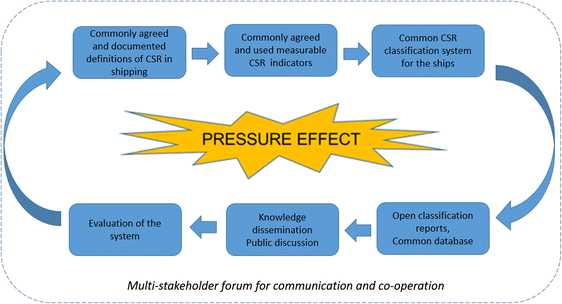

This analysis indicates a need for multi-disciplinary enquiry to (1) provide a common definition/formal written codes of CSR, (2) provide indicators that allow the ranking of shipping companies based on their safety and environmental performance, which would aid, for instance, banks, financers, and nomenclature societies to finance responsible companies and practices, and (three) develop mutual classification systems, in co-operation with other stakeholders, that provide data, for example, for customers and consumers on CSR practices and assist them to brand choices between responsible and "irresponsible" companies (Fig. iii).

To be effective, this study suggests that the CSR initiatives should take a comprehensive 3-factor approach to responsibleness past considering ecology and social responsibility as well as safety (Fig. 2). A holistic set of globally agreed and transparently used indicators would provide a functional tool kit that can assist aircraft companies to evaluate and improve their CSR practices, also every bit help all the stakeholders to make responsible decisions in their business and everyday life. This would automatically create pressure for aircraft companies past strengthening stakeholder power (Figs. 2 and 3).

Suggested holistic indicator approach to define, mensurate, and communicate the CSR in the shipping industry

Suggested global multi-stakeholder forum enhancing the stakeholder power in the aircraft sector, past promoting environmental and social responsibility in the shipping industry

This report farther indicates that a multi-stakeholder arroyo is particularly of import in terms of issues that take and so far been largely neglected by the shipping industry, equally multi-stakeholder force per unit area tin can aid in widening societal goals. As demonstrated, NGO alliances tend to focus on a wide variety of problems and play a critical function in opening infinite for wider discourses on sustainability, such every bit social and economical justice, human rights, human being wellness and working conditions, and the transparency of industry practices. Ultimately, transport is a social and political question and depicts the way guild chooses to live and trade. Similarly, the interdisciplinary scientific customs could take an important role in initiating dialog and communication on the risks and the environmental impacts of maritime traffic, including questions on who should pay for the investment in new technologies to reduce risks or who should pay for the environmental impacts of aircraft or the damages acquired past possible oil spills.

The role of the different regulatory bodies remains highlighted, as overestimating the function of stakeholder power might release pressure on governments and corporations to enact changes (Dauvergne and Lister 2010). Therefore, the analysis suggests that the IMO can be considered as an important ally for the stakeholders, and that it is essential for the IMO to accept the diverse environmental and social demands seriously in moving towards sustainable industry practices. This written report suggests the need for the IMO to proactively support and promote multi-stakeholder co-performance both on international and local/regional scales, including local initiatives and joint actions, such equally the germination of multi-stakeholder alliances in Prince William Audio, Alaska (Merrick et al. 2001, 2002), likewise every bit international alliances, such as the Sustainable Aircraft Initiative (SSI) and the Globe Sea Council (WOC). Moreover, EU legislation on improving seafarers' rights, just applies to ships flying nether the Eu flag, and its effects on the residual of the industry remain unclear: nether globalization and increased competitiveness, with the use of multinational crews together with Flags of Convenience, improving seafarers' rights and considering the human element remain equally major challenges for the shipping industry globally, and require regulatory support at both national and international levels.

Conclusions

The aim of this study was to investigate how stakeholders can promote environmental and social responsibility in the aircraft industry. The study revealed the potential for multi-stakeholder force per unit area to promote environmental and social responsibility in the aircraft industry: multi-stakeholder pressure level based on both chief/financial and secondary/non-fiscal stakeholder action promotes the adoption, implementation, and enforcement of corporate social responsibleness practices and tin push for improved legislation. Multi-stakeholder co-operation tin widen the telescopic of focus of CSR initiatives by drawing farther attention to problems that have largely been left unaddressed including, the often-invisible environmental impacts of dry-bulk shipping or social issues, such equally, improving the rubber and rights of seafarers or the need for increased transparency of operations.

The written report has been express by its focus on corporate social responsibility in the shipping industry in general: due to the diverse nature of the manufacture, further research on CSR implementation at a finer level is needed, i.e. on the differences betwixt operational types or between regions. Similarly, we accept defined corporate social responsibility practices largely in terms of safety as well as environmental and social responsibility, but have paid less attending to the third pillar of CSR, the economical benefits:CSR practices need to be profitable for shipping companies. This written report, however, suggests that in the face of stakeholder demands, the shipping manufacture needs to widen its societal goals and increasingly demonstrate the responsibility of its practices in a transparent manner.

Finally, multi-stakeholder initiatives crave time and resource. This report has demonstrated that such initiatives exist at regional too as international scales, merely further inquiry is needed on the effectiveness of multi-stakeholder co-operation, including studies on the procedure, scope, and depth of stakeholder involvement. In moving towards a more responsible shipping manufacture, the IMO needs to pay increasing attending to multi-stakeholder demands and initiatives. The importance of responsible practices will be further accentuated in the future due to the expected growth in maritime traffic and the potential opening of new routes in the vulnerable environment of the Arctic Ocean.

References

-

Acciaro Yard (2012) Ecology social responsibility in aircraft: is information technology here to stay? The Quarterly Newsletter of the International Association of Maritime Economists 32(1):27–30

-

Aguilera RV, Rupp DE, William SA, Ganapathi J (2007) Putting the Due south back in corporate social responsibility: amultilevel theory of social modify in organizations. Acad Manag Rev 32(3):836–863

-

Aguinis H, Glavas A (2012) What we know and Don't know virtually corporate social responsibility: areview and research agenda. J Manag 38(iv):932–968

-

Andersson KS, Brynolf JF, Lindgren, Wilewska-Bien One thousand (2016) Shipping and the surroundings: improving environmental operation in marine transportation. Springer, Heidelberg

-

Baltic Marine Surround Protection Commission (HELCOM) (2016). Passenger Send Sewage Discharges into the Baltic Sea Will Be Banned. http://www.helcom.fi/news/Pages/Passenger-ship-sewage-discharges-into-the-Baltic-Sea-will-be-banned.aspx. Accessed 28 July 2016

-

Bhattacharya S (2011) Sociological factors influencing the do of incident reporting: the case of the aircraft manufacture. Employee Relations 34(1):iv–21

-

Buysse G, Verbeke A (2003) Proactive environmental strategies: astakeholder management perspective. Strateg Manag J 24:453–470

-

Byster LA, Smith T (2006) From grassroots to global. In: Smith T, Sonnenfeld DA, Pellow DN (eds) Challenging the transport: labor rights and ecology justice in the global electronics manufacture. Temple University Printing, Philadelphia, pp 111–119

-

Cartwright R, Baird C (1999) The development and growth of the cruise industry. Butterworth/ Heinemann, Oxford

-

Clarkson MBE (1995) A stakeholder framework for analyzing and evaluating corporate social performance. Acad Manag Rev 20(one):92–117

-

Clean Cargo Working Group (2016) Clean Cargo Working Grouping | Collaboration Groups | BSR. http://www.bsr.org/en/collaboration/groups/clean-cargo-working-group. Accessed on 4 August 2016

-

Connor T (2004) Time to scale upwardly cooperation? Trade unions, NGOs, and the international anti-sweatshop movement. Evolution in Practise 14(1–2):61–70

-

Dahlsrud A (2008) How corporate social responsibility is divers: an analysis of 37 definitions. Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag 15:1–13

-

Dauvergne P, Lister J (2010) The prospects and limits of eco-consumerism: shopping our way to less deforestation? Organi Environ 23(ii):132–154

-

Dauvergne P, Lister J (2013) Eco-business: abig-brand takeover of sustainability. MIT Press, London

-

Delmas Thousand, Toffel MW (2004) Stakeholders and ecology management practices: an institutional framework. Bus Strateg Environ xiii(4):209–222

-

Denktas-Sakar D, Karatas-Cetin C (2012) Port sustainability and stakeholder Management in Supply Chains: aframework on resources dependence theory. Asian J Shipping Logist 28(three):301–320

-

Det Norske Veritas (2014) Corporate Social Responsibleness and the Shipping Industry—project Study. Report No 2004–1535. http://www.he-alert.org/filemanager/root/site_assets/standalone_pdfs_0355-/HE00375.pdf. Accessed 5 March 2016

-

European Transport Workers' Federation (2015)Maritime ship. http://world wide web.etf-europe.org/seafarers.cfm. Accessed 24 July 2015

-

Fafaliou I, Lekakou Chiliad, Theotokas I (2006) Is the European aircraft industry aware of corporate social responsibility? The case of the Greek-owned Short Sea shipping companies. Mar Policy thirty:412–419

-

Forum for the Future (2017) Sustainable Shipping Initiative. http://www.forumforthefuture.org/project/sustainable-shipping-initiative/overview. Accessed 31 May 2017

-

Freeman RE (1984) Strategic management: astakeholder approach. Pitman, Boston

-

Frooman J (1999) Stakeholder influence strategies. Acad Manag Rev 24(2):191–205

-

Green Award (2009) Green Award: The Pride of the Oceans. http://world wide web.greenaward.org/greenaward/. Accessed 14 January 2016

-

Greenpeace (2010) Sweet Success for Kit Kat Campaign: You Asked, Nestlé Has Answered.http://www.greenpeace.org/international/en/news/features/Sweet-success-for-Kit-Kat-campaign/. Accessed 22 July 2016

-

Haapasaari P, Helle I, Lehikoinen A, Lappalainen J, Kuikka South (2015) Proactive approach for maritime safety policy making for the Gulf of Finland: seeking best practices. Mar Policy lx:107–118

-

Hetherington C, Flin J, Mearns K (2006) Safety in shipping: the human element. J Saf Res 37:401–411

-

Hosmer LT, Kiewitz CK (2005) Organizational justice: abehavioral science concept with critical implications for business ethics and stakeholder theory. Bus Ethics Q xv(1):67–91

-

IMO (2016) Reduction of GHG emissions from Ships. http://www.ics-aircraft.org/docs/default-source/Submissions/reduction-of-ghg-emssions-from-ships.pdf Accessed 31 May 2017

-

International Chamber of Aircraft (ICS) (2014) Shipping, World Merchandise and the Reduction ofCO2 Emissions: United nations Framework Convention on Climate change (UNFCCC).http://www.ics-aircraft.org/docs/default-source/resources/ecology-protection/shipping-world-trade-and-the-reduction-of-co2-emissions.pdf?sfvrsn=6. Accessed 14 January 2016

-

Ionescu-SomersA, EndersA (2012) How Nestlé Dealt with a Social Media Entrada against It. Fiscal Times. http://world wide web.ft.com/cms/south/0/90dbff8a-3aea-11e2-b3f0-00144feabdc0.html#axzz4F9G3f64e. Accessed 22 July 2016

-

Kong N, Salzmann O, Steger U, Ionescu- Somers A (2002) Moving business organisation/industry towards sustainable consumption: the role of NGOs. Eur Manag J 20(two):109–127

-

KunnaalaV, RasiM, StorgårdJ (2013) Corporate Social Responsibility and Shipping: Views of Baltic Body of water Shipping Companies on the Benefits of Responsibility.Publications of the Centre for Maritime Studies, Turku University

-

Kuronen, J, TapaninenU (2009) Maritime Safety in the Gulf of Finland- Review on Policy Instruments. Publications of the Centre for Maritime Studies, University of Turku

-

Lai One thousand, Lun VYH, Wong CWY, Cheng TCE (2011) Green aircraft practices in the shipping industry: conceptualization, adoption, and implications. Resour Conserv Recycl 55(6):631–638

-

Lister J, Poulsen RT, Ponte S (2015) Orchestrating environmental governance in maritime shipping. Glob Environ Chang 34:185–195

-

Lloyd'south Register Marine (2016) Lloyd'due south Register Marine. http://world wide web.lr.org/en/marine/. Accessed fourteen Jan 2016

-

Lois P, Wang J, Wall A, Ruxton T (2004) Formal safety assessment of cruise ships. Tour Manag 25(1):93–109

-

Lyon TP, Montgomery AW (2015) The ways and end of greenwash. Organ Environ 25(2):223–249

-

McWilliamsA, Siegel DS, Wright PM (2006) Invitee editors' introduction: corporate social responsibility: strategic implications. J Manag Stud 43(ane):1–xviii

-

Merrick JRW, van Dorp JR, Harrald J, Mazzuchi T, Spahn JE, Grabowski Yard (2001) A systems approach to managing oil transportation run a risk in Prince William sound. Organisation. Engineering three(three):128–142

-

Merrick JRW, van Dorp JR, Mazzuchi T, Harrald J, Spahn JE, Grabowski Yard (2002) The Prince William sound chance assessment. Interfaces 32(6):25–40

-

Mitchell RK, Agle BR, Wood FJ (1997) Toward a theory of stakeholder identification and salience: defining the principle of who and what really counts. Acad Manag Rev 22(iv):853–886

-

NGO Shipbreaking Platform (2016a) Off the Beach. http://www.offthebeach.org/. Accessed 29 July 2016

-

NGO Shipbreaking Platform (2016b) NGO Shipbreaking Platform Press Release – European Commission Report Recommends the Introduction of a Ship Recycling License. http://www.shipbreakingplatform.org/press-release-european-committee-written report-recommends-the-introduction-of-a-ship-recycling-license/. Accessed 29 July 2016

-

Norwegian Shipowner'due south Clan (NSA) (2016) Responsible Recycling of Ships.https://www.rederi.no/en/aktuelt/2016/ansvarlig-resirkulering-av-skip/. Accessed 3 May 2016

-

Oceana (2004) California Passes Legislation to Stop Cruise Ship Sewage Dumping. http://oceana.org/press-heart/press-releases/california-passes-legislation-end-prowl-ship-sewage-dumping. Accessed 22 July 2016

-

Phillips RA, Freeman RE, Wicks A (2003) What stakeholder theory is not. Autobus Ethics Q 12(4):479–502

-

Poulsen RT, Ponte South, Lister J (2016) Buyer-driven greening? Cargo-owners and environmental upgrading in maritime aircraft. Geoforum 68:57–68

-

Progoulaki M, Theotokas I (2010) Human being resource direction and competitive reward: an application of resources-based view in the aircraft industry. Mar Policy 34(three):575–582

-

Ranängen H, Zobel T (2014) Revisiting the 'how' of corporate social responsibility in extractive industries and forestry. J Clean Prod 84:299–312

-

Raphael C, Smith T (2006) Importing extended producer responsibility for electronic equipment into the United States. In: Smith T, Sonnenfeld DA, Pellow DN (eds) Challenging the ship: labor rights and environmental justice in the global electronics industry. Temple University Press, Philadelphia, pp 247–259

-

Roe MS (2008) Condom, security, the environment and shipping: the problem of making constructive policies. WMU J Marit Aff 7(i):263–279

-

Roe MS (2013) Maritime governance and policy-making: the need for process rather than grade. Asian J Aircraft Logist nine(2):167–186

-

Sampson H, Bloor G (2012) The effectiveness of global regulation inthe shipping industry:acritical instance written report. Revista Latino-americana de Estudos do Trabalho 17(28):45–72

-

Sharma S, Henriques I (2005) Stakeholder influences on sustainability Practises in the Canadian Forest products industry. Strateg Manag J 26:159–180

-

Trident Alliance (2016) Trident Brotherhood. http://www.tridentalliance.org/. Accessed 25 July 2016

-

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) (2015) Review of Maritime Transport. http://unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/rmt2015_en.pdf. Accessed 16 October 2016

-

World Ocean Council (WOC) (2017) World Sea Council - The International Business organization Alliance For Corporate Body of water Responsibility. http://oceancouncil.org/. Accessed 08 June, 2017

-

Wuisan L, Leeuwen J, van CSA K (2012) Greening international shipping through individual governance: acase report of the clean shipping project. Mar Policy 36:165–173

-

WWF (2015) Better Shipping Practices. http://wwf.panda.org/what_we_do/how_we_work/conservation/marine/solutions/sustainable_use/shipping/. Accessed 22 July 2016

-

Yliskylä-Peuralahti J, Gritsenko D (2014) Bounden rules or voluntary deportment? A conceptual framework for CSR in shipping. WMU J Marit Aff 13:251–268

-

Yliskylä-Peuralahti J, Gritsenko D, Viertola J (2015) Corporate social responsibility and quality governance in shipping. Ocean Yearbook 29:417–440

Acknowledgements

The piece of work of T. Parviainen was supported financially by the Finnish Maritime and Shipping Foundation, the Finnish Foundation for Nature Conservation, and the Eu'south Key Baltic Interreg Central Baltic 2014–2020 Programme (project number 94) "30MILES." The research was also supported by the European Union's Primal Baltic Interreg Four A Programme (project number CB38) "Minimizing Risks of Maritime Oil Transport by Holistic Rubber Strategies."

We would like to thank the bearding reviewers for their helpful comments. We would also similar to thank Valtteri Laine (HELCOM) and Vappu Kunnaala-Hyrkki (Turku University) for their support and guidance. An before version of this paper was presented at the CHIP and MariePRO project "Sustainable Shipping" seminar held by Brahea Center, May 2016, Turku Academy.

Author information

Affiliations

Corresponding writer

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed nether the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution iv.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/past/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided y'all give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Reprints and Permissions

About this commodity

Cite this article

Parviainen, T., Lehikoinen, A., Kuikka, S. et al. How tin stakeholders promote environmental and social responsibleness in the shipping industry?. WMU J Marit Affairs 17, 49–lxx (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13437-017-0134-z

-

Received:

-

Accustomed:

-

Published:

-

Issue Engagement:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s13437-017-0134-z

Keywords

- Corporate social responsibleness

- Shipping

- Stakeholder theory

- Multi-stakeholder framework

Source: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s13437-017-0134-z