Faiz Ahmed Faiz English Poetry

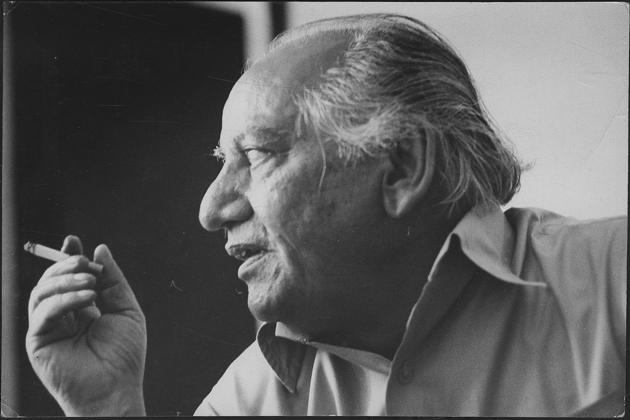

Poet of protest, Faiz Ahmad Faiz

Faiz, wrote compellingly on events that shaped the destiny of the subcontinent; he also brought a new internationalism to Urdu poetry

Updated on Jan 10, 2020 08:02 PM IST

Hindustan Times | Rakhshanda Jalil

Politics and history are said to be commensurate. At the worst of times when upheaval and change are the order of the day, so are politics and poetry. There can be no better example of this axiom in the 20th century than the poetry of Faiz Ahmad Faiz. He wrote, prolifically and compellingly, on the events that shaped the destiny of the subcontinent; apart from his prodigious output as a poet, he also wrote newspaper editorials and articles and gave interviews on a range of subjects that, taken together, reveal a highly political mind beneath the poet's persona and the astonishing range of his concerns and interests.

His father had been educated abroad – in Cambridge and Lincoln's Inn – but not Faiz. Born into straitened circumstances on February, 13, 1911, in Sialkot, Faiz received his early education at the city's Murray College (a landmark institution run by the Church of Scotland, where the poet Iqbal too had studied). He then joined the Government College in Lahore where he studied Arabic, English literature and philosophy.

In 1935, he joined the MAO College, Amritsar, as a teacher of English. Here, Faiz was drawn to the charismatic Rashid Jahan, wife of the vice-principal, Comrade Mahmuduzzafar. In her home he met communists and their sympathisers – both from the Punjab as well as visitors from Aligarh, Lucknow and Mahmuduzzafar's friends from England. During the Amritsar days, he got drawn into the trade union and civil liberties movements – concerns that would occupy him for the rest of his life. And it was here that he got drawn into the great debate of his day: Art For Art's Sake vs. Art For Life's Sake. It was possibly in Amritsar, too, that Faiz read the Communist Manifesto, banned in India but smuggled in by communist groups and made available in universities. It marked a turning point in his life, and poetry.

Faiz brought a new internationalism to Urdu poetry, for though the Urdu poet of the turn of the century had spoken of tremors in the Muslim world, it was only insofar as it concerned the Muslims of India. Faiz was saying it was as much his concern as anybody else's when someone somewhere oppressed the weak, or the mighty system crushed the lone voice of dissent. When Julius and Ethel Rosenberg were sent to the electric chair in 1953 on charges of being Soviet agents in America, Faiz wrote his hauntingly evocative Hum jo tareek raahon mein mare gaye (We who were executed in the dark lanes). Similarly, his ode to Africa, written in 1955, Aa Jao Africa (Come, Africa), is an ode to oppressed people everywhere; it was to show the way towards increasing internationalism in his range of interests.

In later years, Faiz would write with equal passion about Palestine, Namibia and Chile and justify it thus: '... as a writer or an artist, even though I run no state and command no power, I am entitled to feel that I am my brother's keeper, and my brother is the whole of mankind. And this is the relevance to me of peace, of freedom, of detente and the elimination of the nuclear menace. But out of this vast brotherhood, the nearest to me and dearest are the insulted and the humiliated, the homeless and the disinherited, the poor, the hungry and the sick at heart.'

It is precisely for these – the insulted and the humiliated – that the solemn, sonorous, eminently sing-able Hum Dekhenge is written. It contains a promise and a prophecy: one day the oppressed will occupy their rightful place when the tyrants will be vanquished and Truth shall prevail. Written in 1979 in response to General Ziaul Haq's repressive regime, it is as much a song for his own country reeling under a dictator as for people anywhere in the world fighting oppression. And that is why it has found a life beyond its own time and circumstance, as good poetry invariably does.

Faiz evolved a complex system of images, drawn from the classical Persian tradition that seemed on the face of it 'harmless' enough and could escape detection by hawk-eyed censors but had sharp political overtones.

For instance, ashiq (lover) became patriot and revolutionary; mashuq (beloved) used for the country or people; raqib (rival) used interchangeably for imperialism, capitalism, tyranny, exploitation; ishq (love) became revolutionary zeal; visal or deedar (union with the beloved) revolution or social change; hijr or firaq (separation) oppression by the state; rind (libertine) rebel; sharab, maikhana, pyala, saqi (wine, tavern, cup, cup-bearer) sources of social and political awareness; haq (truth) socialism; khirad (empirical knowledge) capitalism or the establishment; zanjir (chain) chain of slavery; bulbul (nightingale) nationalist poet; gul (rose) political ideal; but (idol) present-day rulers; and the Kaaba, any sacred space, even the country.

Rakhshanda Jalil is a writer, translator and literary historian.

Get our Daily News Capsule

Get our Daily News Capsule

Thank you for subscribing to our Daily News Capsule newsletter.

Close Story

- Horoscope Today

- Today Panchang

- Delhi's AQI

- India Covid Cases

- Delhi Air Pollution

- Bigg Boss 15

Story Saved

Faiz Ahmed Faiz English Poetry

Source: https://www.hindustantimes.com/books/poet-of-protest-faiz-ahmad-faiz/story-xdjypixP4kn6v26TxDop8L.html